Sunday, June 16, 2013

Saturday, June 15, 2013

Windows 8’s lock screen is very at home on a tablet, but it can also be used on laptops and desktops. The lock screen is not just a background image – it contains widgets that display quick notifications.

These widgets, known as lock screen apps, allow you to view information – such as new emails, weather, calendar appointments, instant messages or social updates – without even unlocking your PC.

Select a Lock Screen Background

Lock screen settings are located in the PC setting application on Windows 8. To access it, open the Settings charm (press Windows Key + I to quickly open the Settings charm from anywhere in Windows) and select Change PC settings.

Select the Personalize category and select Lock screen. Click (or tap) one of the provided background images or use the Browse button and select any image from your computer, Bing, SkyDrive, or even your camera.

If you want more features, try using the Chameleon app located in the Windows Store. It can watch “photo of the day”-type services and automatically change your lock screen background on a schedule, a feature not included with Windows 8.

Configure Lock Screen Apps

Lock screen widgets – known as “lock screen apps” in Windows 8 – allow you to view information at a glance. Apps added to the lock screen are allowed to run in the background when your PC is locked so they can fetch new, updated information and display it on the lock screen.

You can configure the list of lock screen apps from the Lock screen apps section below the lock screen background chooser. Click (or tap) an icon and select the app you want in that location. You can get more widgets by installing more Windows Store apps – apps can choose to include lock screen integration. If you do not want any lock screen apps – or just want a few – you can select the Don’t show quick status here option.

You can also choose an app to show a more detailed status. For example, when you choose to display a detailed weather status, you will see the weather displayed in text on your lock screen.

That’s it for customizing the lock screen – it’s all about background images and lock screen apps. However, with custom backgrounds and apps, each person’s lock screen could look different.

Your computer stores low-level settings like the system time and hardware settings in its CMOS. These settings are configured in the BIOS setup menu. If you’re experiencing a hardware compatibility issue or another problem, you may want to try clearing the CMOS.

Clearing the CMOS resets your BIOS settings back to their factory default state. In most cases, you can clear the CMOS from within the BIOS menu. In some cases, you may have to open your computer’s case.

Use the BIOS Menu

The easiest way to clear the CMOS is from your computer’s BIOS setup menu. To access the setup menu, restart your computer and press the key that appears on your screen – often Delete or F2 – to access the setup menu.

If you don’t see a key displayed on your screen, consult your computer’s manual. Different computers use different keys. (If you built your own computer, consult your motherboard’s manual instead.)

Within the BIOS, look for the Reset option. It may be named Reset to default, Load factory defaults, Clear BIOS settings, Load setup defaults, or something similar.

Select it with your arrow keys, press Enter, and confirm the operation. Your BIOS will now use its default settings – if you’ve changed any BIOS settings in the past, you’ll have to change them again.

Use the CLEAR CMOS Motherboard Jumper

Many motherboards contain a jumper that can be used to clear CMOS settings if your BIOS is not accessible. This is particularly useful if the BIOS is password-protected and you don’t know the password.

The exact location of the jumper can be found in the motherboard’s (or computer’s) manual. You should consult the manual for more detailed instructions if you want to use the motherboard jumper.

However, the basic process is fairly similar on all computers. Flip the computer’s power switch to off to ensure it’s not receiving any power. Open the computer’s case and locate the jumper named something like CLEAR CMOS, CLEAR, CLR CMOS, PASSWORD, or CLR PWD – it will often be near the CMOS battery mentioned below. Ensure you’re grounded so you don’t damage your motherboard with static electricity before touching it. Set the jumper to the “clear” position, power on your computer, turn it off again, set the jumper to the original position – and you’re done.

Reseat the CMOS Battery

If your motherboard does not have a CLEAR CMOS jumper, you can often clear its CMOS settings by removing the CMOS battery and replacing it. The CMOS battery provides power used to save the BIOS settings – this is how your computer knows how much time has passed even when it’s been powered-off for a while – so removing the battery will remove the source of power and clear the settings.

Important Note: Not all motherboards have removable CMOS batteries. If the battery won’t come loose, don’t force it.

First, ensure the computer is powered off and you’re grounded so you won’t damage the motherboard with static electricity. Locate the round, flat, silver battery on the motherboard and carefully remove it. Wait five minutes before reseating the battery.

__________________________________________________________________

Clearing the CMOS should always be performed for a reason – such as troubleshooting a computer problem or clearing a forgotten BIOS password. There’s no reason to clear your CMOS if everything is working properly.

We already live in the future. We have handheld devices that use satellites to pinpoint our precise locations almost anywhere on the planet. But have you ever wondered just how GPS works?

GPS devices don’t actually contact satellites and transmit information to them. They only receive data from satellites – data that’s being always-transmitted. However, GPS isn’t the only way devices can determine your location.

From Satellites to the Palm of Your Hand

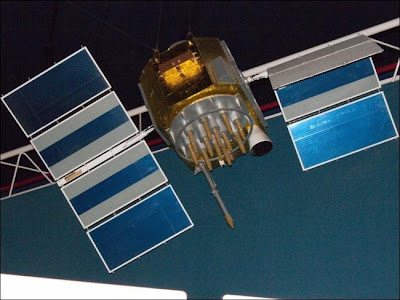

The global positioning system was originally created by the United State for military use, but was eventually opened up to civilian use. At least 24 GPS satellites are always in orbit around the Earth, and they’re constantly broadcasting data.

The satellites are arranged in orbit such that four satellites are visible in the sky from any point on Earth. (You can’t actually see them, but there’s a direct path for the radio transmissions.) This means that GPS won’t work if the signals are being blocked – you will want a fairly direct path between you and the sky. In an underground bunker or in a cave under a mountain, it won’t work.

GPS satellites are constantly transmitting radio signals towards the Earth. Each transmission includes the location of the GPS satellite and the time the signal was sent. Each satellite has an atomic clock onboard, so the time is very precise.

How GPS Determines Your Location

A device with built-in GPS – whether it’s a dedicated in-car GPS navigation unit or a smartphone – only acts as a GPS receiver. A device with GPS isn’t actually “contacting” satellites to determine its location. Instead, it’s just listening for the radio signals that are being broadcast from these satellites all the time.

A GPS receiver “listens” for signals from four or more satellites. Signals from the closer satellites will arrive sooner, while signals from the farther satellites will arrive later. (The actual time difference is very small, but can be detected by the GPS receiver.) By comparing the time the signal was broadcast and the time the signal arrived, the receiver can estimate its relative distance from all four satellites. Using trilateration, the receiver can then determine its location.

Trilateration may sound a bit complicated, but it’s actually fairly simple. Imagine if someone told you you were 500 miles from New York, 800 miles from Miami, and 700 miles from Kansas City. With this information, you could determine a region that is the correct distance from all of these cities and estimate your current location. If we told you your distance from a fourth city, you could estimate your location even more precisely. That’s trilateration in a nutshell, and it’s what GPS receivers are doing whenever you use them.

Alternatives to GPS

GPS isn’t the only way devices can estimate your current location. The 911 service uses cell tower strength information to triangulate the position of mobile phones. This works in a similar way – by measuring the signal strength differences between multiple cell towers, your device can estimate your current location.

Some devices can also use a Wi-Fi based positioning system (WPS) to determine their current location. Google’s street view trucks drive around, capturing the names of nearby access points and their relative strengths at certain locations. Your smartphone scans for nearby wireless networks, then sends a list of their names and signal strengths to Google’s servers. Google uses their database and estimates where you are. (Google isn’t the only provider of Wi-Fi-based positioning system data, but it’s the one most people will be familiar with.) This can be particularly convenient in indoor locations GPS signals can’t reach.

The GPS system isn’t the only network of satellites that can be used for positioning, either. Russia has its own GLONASS system and China has BDS. Europe is also working on its own alternative to GPS, known as Galileo. GPS could be shut down or restricted in times of war or conflict, so nations want their own satellites to be self-sufficient.

__________________________________________________________________

GPS on its own isn’t a privacy concern – for example, if you have an old GPS unit for your car, it likely isn’t capable of transmitting your location. However, GPS can be a privacy concern when combined with transmitting technology. GPS tracking devices don’t just use GPS receivers – they store the GPS data for later retrieval or transmit the GPS data.

If you have a single wired Internet connection – say, in a hotel room – you can create an ad-hoc wireless network with Ubuntu and share the Internet connection among multiple devices. Ubuntu includes an easy, graphical setup tool.

Unfortunately, there are some limitations. Some devices may not support ad-hoc wireless networks and Ubuntu can only create wireless hotspots with weak WEP encryption, not strong WPA encryption.

Setup

To get started, click the gear icon on the panel and select System Settings.

Select the Network control panel in Ubuntu’s System Settings window. You can also set up a wireless hotspot by clicking the network menu and selecting Edit Network Connections, but that setup process is more complicated.

If you want to share an Internet connection wirelessly, you’ll have to connect to it with a wired connection. You can’t share a Wi-Fi network – when you create a Wi-Fi hotspot, you’ll be disconnected from your current wireless network.

To create a hotspot, select the Wireless network option and click the Use as Hotspot button at the bottom of the window.

You’ll be disconnected from your existing network. You can disable the hotspot later by clicking the Stop Hotspot button in this window or by selecting another wireless network from the network menu on Ubuntu’s panel.

After you click Create Hotspot, you’ll see an notification pop up that indicates your laptop’s wireless radio is now being used as an ad-hoc access point. You should be able to connect from other devices using the default network name – “ubuntu” – and the security key displayed in the Network window. However, you can also click the Options button to customize your wireless hotspot.

From the wireless tab, you can set a custom name for your wireless network using the SSID field. You can also modify other wireless settings from here. The Connect Automatically check box should allow you to use the hotspot as your default wireless network – when you start your computer, Ubuntu will create the hotspot instead of connecting to an existing wireless network.

From the Wireless Security tab, you can change your security key and method. Unfortunately, WPA encryption does not appear to be an option here, so you’ll have to stick with the weaker WEP encryption.

The “Shared to other computers” option on the IPv4 Settings tab tells Ubuntu to share your Internet connection with other computers connected to the hotspot.

Even if you don’t have a wireless Internet connection available to share, you can network computers together and communicate between them – for example, to share files.

You’ve probably heard that you always need to use the Safely Remove Hardware icon before unplugging a USB device. However, there’s also a good chance that you’ve unplugged a USB device without using this option and everything worked fine.

Windows itself tells you that you don’t need to use the Safely Remove Hardware option if you use certain settings – the default settings – but the advice Windows provides is misleading.

Quick Removal vs. Better Performance

Windows allows you to optimize your USB device for quick removal or improved performance. By default, Windows optimizes USB devices for quick removal. You can access this setting from the device manager – open the Start menu, type Device Manager, and press Enter to launch it.

Expand the Disk drives section in the Device Manager, right-click your device, and select Properties.

Select the Policies tab in the Properties window. You’ll notice that Windows says you can disconnect your USB device safely without using the Safely Remove Hardware notification icon, so this means you can unplug your USB device without ever safely removing it, right? Not so fast.

Data Corruption Danger

The Windows dialog shown above is misleading. If you unplug your USB device while data is being written to it – for example, while you’re moving files to it or while you’re saving a file to it – this can result in data corruption. No matter which option you use, you should ensure that your USB device isn’t in-use before unplugging it – some USB sticks may have lights on them that blink while they’re being used.

However, even if the USB device doesn’t appear to be in-use, it may still be in-use. A program in the background may be writing to the drive – so data corruption could result if you unplugged the drive. If your USB stick doesn’t appear to be in-use, you can probably unplug it without any data corruption occurring – however, to be safe, it’s still a good idea to use the Safely Remove Hardware option. When you eject a device, Windows will tell you when it’s safe to remove – ensuring all programs are done with it.

Write Caching

If you select the Better Performance option, Windows will cache data instead of writing it to the USB device immediately. This will improve your device’s performance – however, data corruption is much more likely to occur if you unplug the USB device without using the Safely Remove Hardware option. If caching is enabled, Windows won’t write the data to your USB device immediately – even if the data appears to have been written to the device and all file progress dialogs are closed, the data may just be cached on your system.

When you eject a device, Windows will flush the write cache to the disk, ensuring all necessary changes are made before notifying you when it’s safe to remove the drive.

While the Quick Removal option decreases USB performance, it’s the default to minimize the chances of data corruption in day-to-day use – many people may forget to use – or never use – the Safely Remove Hardware option when unplugging USB devices.

Safely Removing Hardware

Ultimately, no matter which option you use, you should use the Safely Remove Hardware icon and eject your device before unplugging it. You can also right-click it in the Computer window and select Eject. Windows will tell you when it’s safe to remove the device, eliminating any changes of data corruption.

__________________________________________________________________

This advice doesn’t just apply to Windows – if you’re using Linux, you should use the Eject option in your file manager before unplugging a USB device, too. The same goes for Mac OS X.

After using Windows 8 for a while, I’ve come to the conclusion that removing the Start button from the Taskbar was a huge mistake. Here’s how to make your own “Start” button that brings up the Metro Start screen—but doesn’t waste any memory at all.

What we’ll be doing is pretty simple—create a script that simulates pressing the Windows key button, make it into an executable, assign an icon, and pin it to the taskbar so that it sorta looks like the Start button, and works the same way. Since nothing is running, no RAM is wasted.

Creating Your Own Windows 8 Start Button

You’ll need to start by downloading and installing AutoHotkey, and then creating a new script with the New –> Autohotkey Script item on the context menu. Once you’ve done that, paste in the following code:

Save the script, and then right-click and choose the Compile Script option, which will create an executable file.

Right-click on the .exe and choose Create Shortcut, and then open up the Shortcut properties screen.

In here you’ll want to browse for the imageres.dll file, which has a lot of pretty icons in it. Here’s the path, which obviously will need to be adjusted if you installed Windows somewhere else.

There’s a Windows flag icon in there, as well as some other icons… and of course, you could use any icon file here if you wanted, including one that you’ve downloaded from somewhere.

Now you’ll want to use the Pin to Taskbar option on the context menu–you’ll probably need to drag it into the right position.

You’ll notice that I choose the Metro-style Window icon, which actually looks pretty cool… but again, you can use any icon you want.

That’s all there is to it—press the button, the Metro Start screen will come up. Zero memory usage, since nothing is running in the background. In fact, you should be able to uninstall AutoHotkey at this point if you want.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

join me on Facebook

Popular Posts

Recent Comments

Followers

Copyright ©

Geek informatics | Powered by Blogger

Design by Azmind.com | Blogger Template by NewBloggerThemes.com